One of the problems presented by the development of the Renewable Hydrogen Economy is what is known as the “dilemma of the chicken and the egg,” in other words, do we need to start with renewable hydrogen production, or demand? Is it necessary to first have the infrastructure or the need to distribute renewable hydrogen?

In my opinion, the real reason that the Renewable Hydrogen Economy has not taken off, is because there is no regulation mandating the blending; everything else is fooling ourselves with grand press announcements that never come true.

Currently, politics and ideology are, without realizing it, playing in favour of maintaining the status quo, favouring those who have their businesses based on oil and natural gas, and those are the people who benefit from what is happening.

In the meantime, in 2023, we have reached a new peak of CO2 emissions, according to studies by the Global Carbon Project (https://www.globalcarbonproject.org/).

Recently, Bloomberg published a study (https://about.bnef.com/blog/hydrogen-offtake-is-tiny-but-growing/) stating that only 10% of projects announced all over the world have an off-taker for their hydrogen in 2030; the rest are still waiting for a customer to move forward.

In my opinion, as I’ve stated before, the “dilemma” can be resolved by regulating the mandatory blending, in the fossil hydrogen and natural gas we consume, of a certain percentage of renewable hydrogen. This mechanism is very well known by the regulators, as it was used to help biofuels take off in the USA, the European Union, and Brazil.

If there were a regulation establishing that all fossil hydrogen and natural gas sold had to include 5% renewable hydrogen, and this was implemented in regions such as the USA, the European Union, and Asia (India, South Korea, and Japan) and Australia, the true Hydrogen Economy would have started, and it would be a reality within 20 years. Note that I refer to 5% measured in energy, not in volume or in mass.

It is only with this hydrogen production volume that we would manage to improve efficiency and reduce costs, while also reducing the costs associated with the necessary equipment (electrolysers, compressors…), the way the costs for wind and photovoltaic energy were reduced. In addition, this would create a market to allow large production countries, such as Chile or others, to export renewable hydrogen.

We must consider that approximately 70% of the cost of renewable hydrogen is the price of electricity. If costs are reduced with large plants and an economy of scale, and the efficiency of the process is improved, the blending percentage could be gradually increased, thus lowering the terrible impact that fossil fuels have on global wealth distribution and on climate change.

Some may say that renewable hydrogen is more expensive than the alternatives, and this would cause loss of competitivity and generate inflation in the short term, but to argue this is to deny the truth shown by statistics.

Currently, renewable hydrogen costs (depending on the price of oil and natural gas) about twice as much as fossil hydrogen and three times as much as natural gas; this distance will be reduced every year. Currently, blending 5% renewable hydrogen into fossil hydrogen would increase fossil hydrogen cost by 5%, and blending that 5% with natural gas would increase the total cost of the product by 10%.

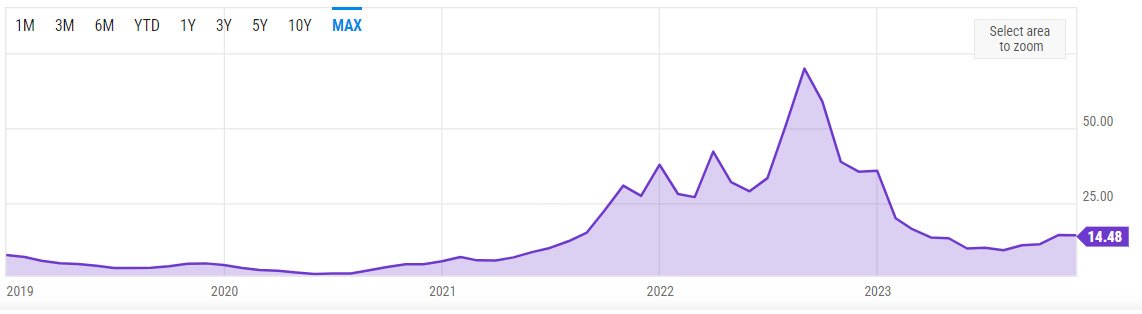

Let us consider, how much have the prices of oil and natural gas varied in the past few years?

For example, the cost of imported natural gas in Europe has increased tenfold in the past three years, an increase of 900%.

It is clear that an oscillation of 5 or 10% is insignificant in the evolution of fossil fuel prices but, additionally, this would reduce fuel dependency, and put us on the path towards a real decarbonisation.

Where are the ideology and the politics that work so hard to block regulation, to the glee of current traditional energy actors?

In other words, if renewable hydrogen is blended with fossil hydrogen or natural has, renewable hydrogen “is soiled” it loses part of its value.

But do we argue the same about the renewable electricity that is poured into the electricity grids? There is electricity that comes from fossil and renewable fuels, and nobody has proposed creating two different networks; further still, even if independent electricity grids were created for fossil and renewable electricity, these would blend when being used…

The idea of not blending renewable and fossil hydrogen, or the former with natural gas (and other fossil fuels) is absurd, and would kill (or at least delay “sine die”) the renewable hydrogen economy.

Renewable hydrogen needs to be progressively blended to introduce it into the market, lower its costs, create an industrial infrastructure and jobs, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and control the price of the fuels we consume.

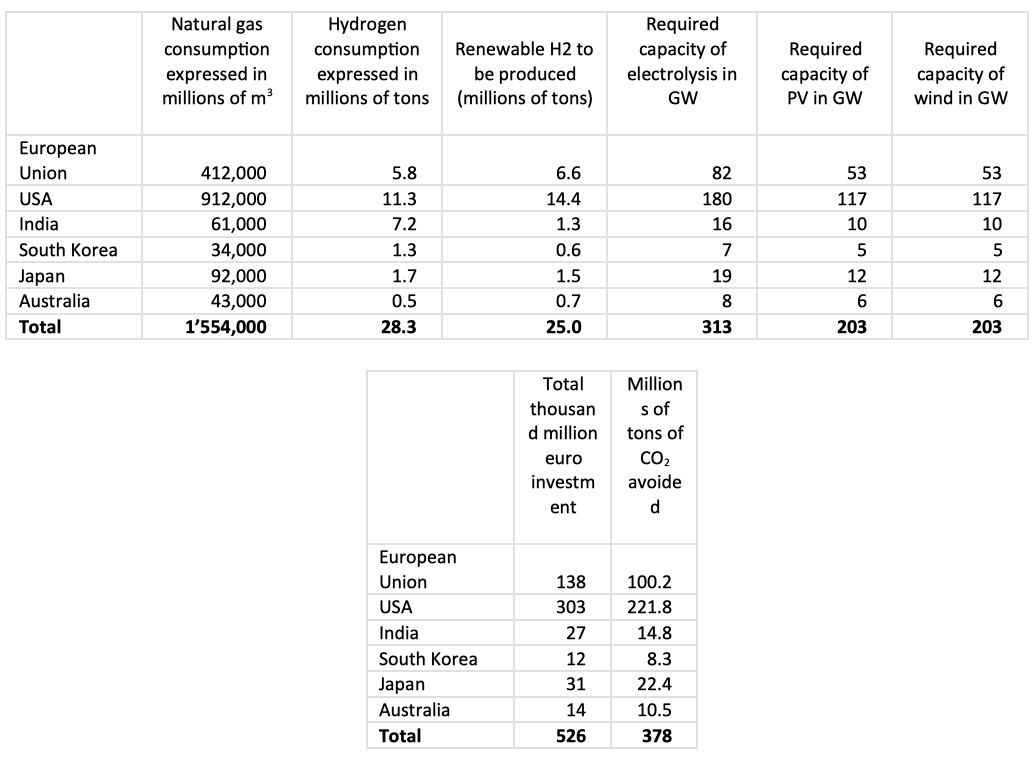

Finally, I will show a quantitative exercise of what I have explained. The following table shows, for the main regions of the world, the current consumption of natural gas and hydrogen, as well as the renewable hydrogen that would have to be produced to substitute 5% of the first two. To summarise, investments of 526 billion euros would be mobilised, we would avoid 378 million tons of CO2 emissions per year, and around 8 million jobs could be created.

In order to get these numbers, I consider that the renewable hydrogen economy will develop in electrolysis facilities vertically integrated with wind, photovoltaic, or other renewable energies, and not connected to the electricity grid.

In this sense, with some exceptions, the premise that renewable hydrogen plants, in order to be viable, need to be connected to the electricity grid to ensure their use 24 hours a day, seven days a week (24/7) is another mistake that makes the hydrogen economy terribly expensive and prevents it from being competitive. This happens when theoretical considerations that are far from reality are assumed.

There are two reasons that favour plants that are not connected to the grid: one is the price of electricity, and the other is that there currently are proven technologies that allow facilities isolated from the grid to function 24/7.

In order for renewable hydrogen to be competitive, the price of a hundred percent renewable energy must not be greater than 2.5 cents of a euro per kilowatt*hour, and renewable hydrogen plants, incorporated into the centre of large (wind or photovoltaic) renewable energy plants would allow for a reduction in costs so we can reach these prices in the medium term. We all know that, today, electricity from the grid is more expensive than that, and even more so if it must be one hundred percent renewable.

And, in relation to continuous operation, battery and high-temperature molten salt technologies, which are perfectly proven, allow us to improve efficiency and produce renewable energy 24/7 in isolated plants.

In sum, although it may annoy and go against the prevailing theories, by simply blending and using vertically integrated plants, we will achieve the real and operational revolution of the renewable hydrogen economy.